Let's talk about sex

What teenagers talk about when they talk about sex.

February 23, 2017

How should we approach some of the pressing issues facing adolescents?

The seminal coming-of-age film thrust the subject of teen sex into the public eye in 1981 with the unsettling awkwardness of love-struck, hormone-fuelled teens fumbling about in the back of a panel van.

For teens, it revealed their world as they see it, navigating through the rough waters of puberty with its experimentation, risk-taking, peer pressure and the emotional rollercoaster of relationships and sex on their passage to adulthood.

For parents, it was a rare, perhaps uncomfortable, glimpse into the sorts of situations they hoped they'd instilled enough sense into their children to avoid.

The film, based on a book of the same name by UOW , also gave audiences a glimpse into what health researchers call the 'sexual economy' - not a phrase thrown around in everyday conversation. Yet, it's a phrase that accurately and bluntly captures the essence of how, for some teens, sex is a tradeable object in the market for approval.

Like all market economies, there are hidden costs and powerful vested interests seeking only their own gratification. For many teens, the costs have come in the form of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as chlamydia, syphilis and gonorrhoea, as well as the spectre of violence toward young women and the emotional bullying of 'slut shaming'.

It won't happen to me

Medical anthropologist Associate Professor Kate Senior, who has spent close to two decades living in remote and rural communities talking to young people about sexuality and health, says not all that much has changed since Puberty Blues first caused waves in mainstream Australia.

Conventional wisdom and published research links high rates of STIs among young people and their seemingly blasé, high-risk sexual behaviour - multiple partners, low condom use and sex while under the influence of alcohol or drugs - with a lack of awareness and concern about the consequences of unsafe sex on their health and wellbeing.

Using a body map, painting a life-sized body outline with feelings, thoughts and responses to situations and creating hypothetical situations, Professor Senior and her colleagues were able to get young people to open up about sensitive topics, lifting the lid on the sex lives of teens.

Professor Senior says their research revealed that issues of self-worth and how young people navigate relationships with each other were strong influences on their sexual behaviour.

"Most young people actually had pretty good knowledge of STIs and safe sex," Professor Senior says. "What was more concerning was the high level of stigma that surrounded getting an STI and the lack of sympathy that young people had for someone that got into this sort of situation.

"Such stigma has important implications for accessing care. As one young person said, 'I'd have to wear a hoody and sunglasses just to go through the door [of the sexual health clinic]'."

Young people, Professor Senior says, seemed to be able to distance themselves from those who were rumoured to have contracted an STI. They often said that people who get STIs were 'dirty', and often associated them with being from another town or another school.

Yet, they felt safer with their own peer group, who they'd often characterise as 'clean', despite having no real knowledge of who they'd slept with and if they'd been tested regularly.

The obvious rejoinder would be that if you can't control nature, at least use a condom to prevent pregnancy and the unwanted transmission of infection.

Making condoms 'cool'

Condoms are cheap, easy to access and use and are an effective protection against disease. Yet, if rates of STIs in Australia remain high, the logical conclusion is they're not being used as much as they should.

Professor Senior is hoping to tackle that issue as part of Project Geldom, a ÁñÁ«ÊÓƵapp of ÁñÁ«ÊÓƵapp-led initiative in partnership with researchers at Swinburne ÁñÁ«ÊÓƵapp, with funds from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

"Young people don't necessarily engage with condoms," Professor Senior says. "They've got a bad rap; they've got a bit of stigma associated with them because we get told over and over again that condoms are about preventing disease, they're about preventing pregnancy.

"They're about the things that they're not, rather than about what they could be and all that's good about them." The aim is to reinvent the condom. To turn a 'should use' into a 'want to use'.

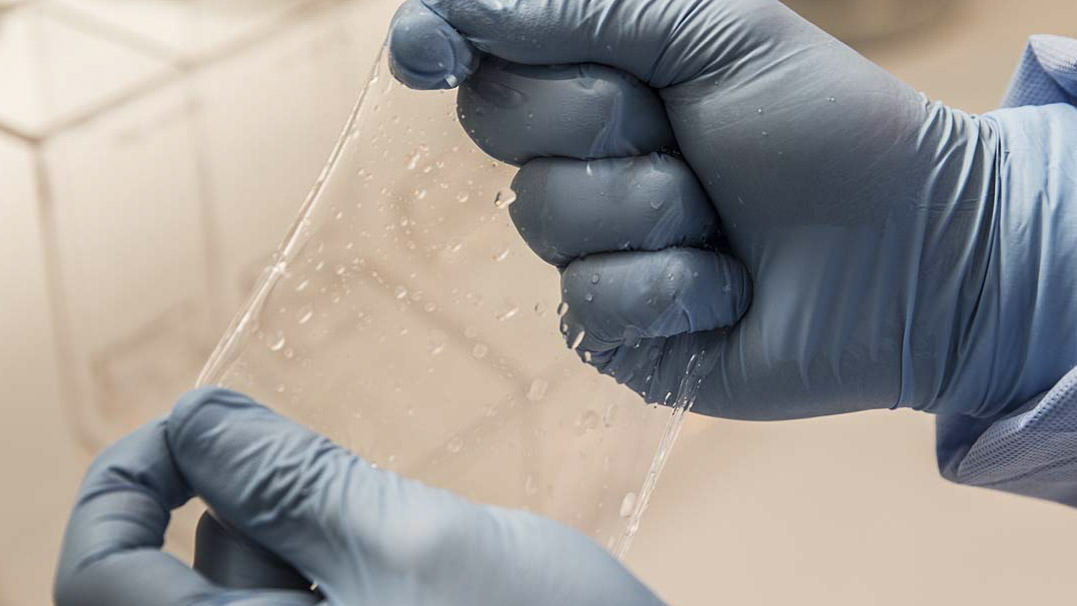

As project leader Associate Professor Robert Gorkin from UOW's Australian Institute for Innovative Materials says, "It's about making sex better." Over the past 18 months, Project Geldom has identified a new material called a hydrogel that has mechanical strength and flexibility, and is an effective barrier to biological material.

It has the added bonus of being more skin-like to touch. Neural testing has shown a preference for the hydrogel-based material.

Now researchers want to include young people in the discussion to make a condom that appeals to their needs and desires.

"This work is about making the condom cool again. I'm not sure the condom has ever been cool.

"We want young people to say, 'that's a great thing', and we want them to be thinking about what the perfect condom could look like."

If the condom could serve to pleasure and protect, it might also help overcome the other important issue for young people in negotiating condom use: in a relationship, no matter how transient, who decides that if it's not on, it's not on?

"What surprised and shocked me about the results of our research was how persistent gender stereotypes are. That essentially was the theme of Puberty Blues, and it remains the theme now," Professor Senior says.

"We heard about emotional manipulation, where the young woman was told, 'if you trust me then we don't need to use a condom'. Young women particularly want to trust their partners and therefore may be pressured into not insisting on safe sex."

This relationship inequality puts young women in a vulnerable position and compromises their feeling of control and being able to negotiate safe sex.

"She often feels that if she asks him to do something he doesn't want to do, that he will just move on," Professor Senior says. "We also found that young women were prepared to put up with a shocking level of intimate violence for the same reason."

A new material called a hydrogel has the potential to make condoms more 'skin-like'. Photo: Paul Jones

Mixed messaging

Intimate violence and sex as power raise the concern that messages about respect and the role of sex in a relationship aren't getting through to young people

"I particularly worry about the perpetuation of the gender stereotypes and the push we are seeing towards hyper-femininity of young women," Professor Senior says. "That's a driving force for us to do what we are doing: to try to create safe opportunities for young people to discuss difficult and sensitive issues and challenge ideas and preconceptions."

Professor Senior says young people are bombarded with conflicting messages, from the misguided to the downright inappropriate and everything in between. The difficulty is providing meaningfully sex education in a way that overcomes stigma and sensitivity.

"Young women found out about sex from their peers and from Dolly magazine, too sad that it no longer exists, and boys were more likely to find out from the internet and porn sites. In many cases, they knew this information wasn't very trustworthy, but they are critical of prevailing sex education that just 'focuses on the organs'. They say it's not relevant to them."

The research has inspired Professor Senior and PhD student Laura Grozdanovski to develop an education game called Life Happens. Designed in collaboration with the Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District's HIV/AIDS and Related Programs unit, Life Happens is an interactive way of helping teenagers and young adults break down the barriers associated with sexuality.

Life Happens is an interactive game to help young people talk about relationships and sexual health. Photo: Paul Jones

Life Happens uses life-size bodies and a series of challenges to guide its characters through a relationship or navigate a sexual health issue. The characters are not assigned a gender - it is up to the participants to decide which gender they want to be - and can deal with both positive and negative challenges when working through the story.

PhD student Laura says the game enables young people to discuss the risks and issues, such as dealing with a sexually transmitted infection or an unexpected pregnancy, and pose hypothetical questions without feeling as if their own vulnerabilities are being laid bare.

"The game really is a safe and inclusive space to talk about experiences without being identified. At the end people are given the opportunity to talk about where they can access information or help on topics raised throughout the game.

"There's no harm in talking about sexuality in general. There's nothing to be ashamed of, everyone has their own experience."

"At the end of the day, you're not alone."